Stomach Ulcer

Overview

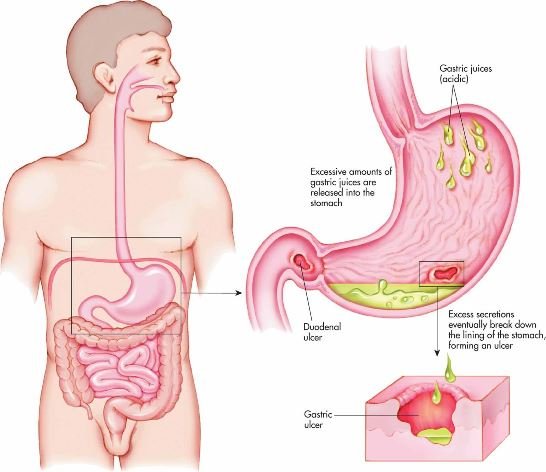

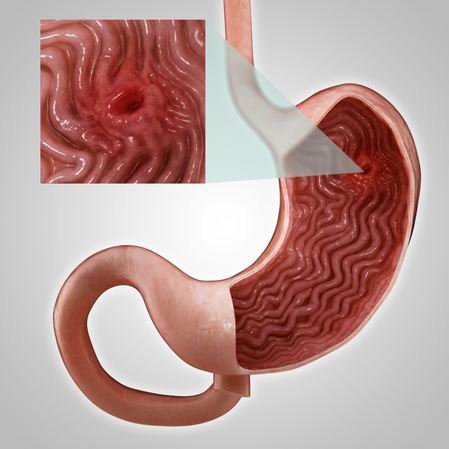

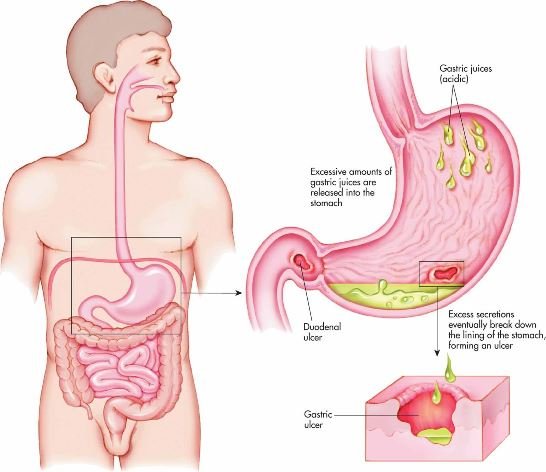

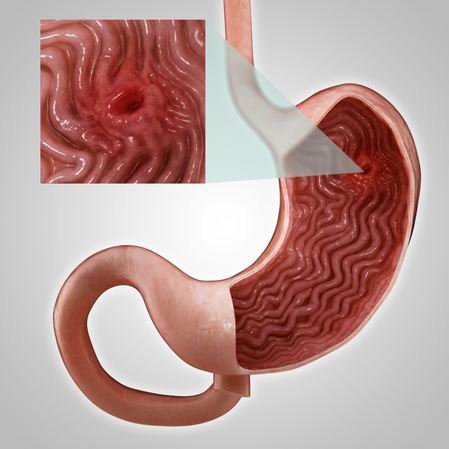

A stomach ulcer, also known as a gastric ulcer, is an open sore that forms in the lining of the stomach. You can also acquire one in your duodenum, which is the initial portion of your small intestine into which your stomach feeds. Peptic ulcers include both duodenal and stomach ulcers. They’re called after pepsin, a digestive enzyme present in the stomach that can sometimes spill into the duodenum.Peptic ulcer disease is exacerbated by these enzymes.

Peptic ulcers develop when the protective mucous lining of your stomach and duodenum is eroded, enabling gastric acids and digestive enzymes to eat away at the walls of your stomach and duodenum. This eventually leads to open sores that are damaged by the acid. They can produce major consequences, such as internal bleeding, if left untreated. They can even bore a hole all the way through over time. There is a medical emergency here.

Causes

Two most common causes:

- Helicobacter pylori : This widespread bacterial illness affects up to half of the world’s population. It typically inhabits the gut. It does not appear to create difficulties in many people. Their gut immune systems keep it under control. However, H. pylori overgrowth affects a percentage of people afflicted. The bacteria continue to grow, producing persistent inflammation and peptic ulcer disease by eating through the stomach lining. H. pylori infection is linked to around 60% of duodenal ulcers and 40% of stomach ulcers.

- Excessive usage of NSAIDs.: NSAID is an abbreviation for “nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.” These include over-the-counter pain relievers including ibuprofen, naproxen, and aspirin. NSAIDs lead to ulcers in a variety of ways. On contact, they irritate the stomach lining and suppress some of the molecules that protect and heal the mucosal membrane. Peptic ulcers affect up to 30% of those who take NSAIDs on a regular basis. Overuse of NSAIDs is responsible for up to 50% of all peptic ulcers.

The following are less prevalent causes of stomach ulcers

- Significant physiological stress. :This is an uncommon disorder in which your stomach produces an excessive amount of gastric acid.

- Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome (ZES) : Stress ulcers in the stomach can be caused by severe sickness, burns, or accidents. Physiological stress alters the PH balance of your body, raising stomach acid. Stress ulcers, as opposed to regular stomach ulcers, grow rapidly in reaction to stress.

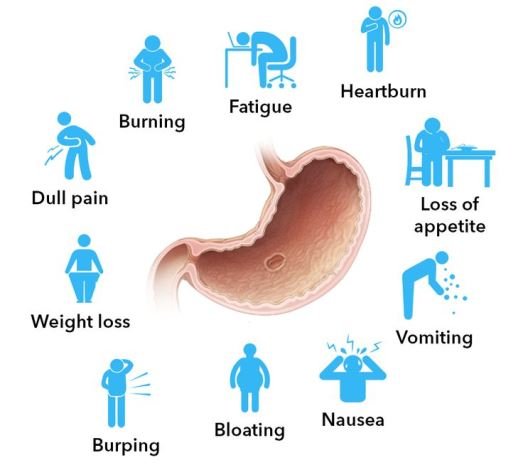

Symtons

Two most common causes:

- Burning stomach pain.

- Helicobacter pyloBloated stomach.ri

- Indigestion, especially of fatty foods.

- Nausea and vomiting.

- Blood in stools or black charry stools in bleeding ulcer

- Bloody vomit

complications of peptic ulcer disease

- Internal bleeding: While most people with ulcers do not experience bleeding, it is the most common consequence. Anemia or serious blood loss can result from a slow bleeding ulcer.

- Perforation: A constantly eroding ulcer by acid might eventually produce a hole in the stomach or intestinal wall. This is both excruciatingly uncomfortable and hazardous. It permits germs from the digestive system to enter the abdominal cavity, which can lead to peritonitis, an infection of the abdominal cavity. The infection is therefore at danger of spreading to the rest of the body (septicemia). This can result in sepsis, a potentially fatal illness.

- Obstruction: An ulcer in the pyloric channel, the thin conduit that connects the stomach to the duodenum, can form an obstruction, preventing food from passing into the small intestine. This is possible after the ulcer has healed. Ulcers that have healed may develop scar tissue that causes them to grow. An ulcer large enough to impede the small intestine might halt digestion, resulting in a variety of negative effects.

- Stomach cancer: Some stomach ulcers might progress to cancer over time. When your ulcer is caused by H. pylori infection, this is more likely. H. pylori is a contributory cause of stomach cancer, which is luckily infrequen

Diagnosis

- Endoscopy

An upper endoscopy exam is expedient because allows healthcare providers to see inside your digestive tract and also take a tissue sample to analyze in the lab. The test is done by passing a thin tube with a tiny camera attached down your throat and into your stomach and duodenum. You’ll have medication to numb your throat and help you relax during the test. Your healthcare provider may use the endoscope to take a tissue sample to test for signs of mucous damage, anemia, H. pylori infection or malignancy. If they take a sample, you won’t feel it.

- Imaging tests. Imaging tests to look inside the stomach and small intestine include

- Upper GI series. An upper GI X-ray exam examines the stomach and duodenum through X-rays. It’s less invasive than an endoscopy. For the X-ray, you’ll swallow a chalky fluid called barium, which will coat your esophagus, stomach and duodenum. The barium helps your digestive organs show up better in black and white images.

- CT scan. Your healthcare provider might recommend a CT scan if they need to see your organs in more detail. A CT scan can show complications such as a perforation in the stomach or intestinal wall. For the test, you’ll lie on a table inside a scanner machine while X-rays are taken. You may drink or have an injection with contrast fluid to make your organs show up better in images.

- Tests for H. pylori. Your healthcare provider might want to test you separately for H. pylori infection. Tests may include

- Blood test. A blood test is a quick and simple way to test for prior H. pylori infection. The lab looks for evidence of antibodies to the bacteria in your blood. It’s not as accurate for diagnosing an active infection, though.

- Stool test. Healthcare providers can also find H. pylori in your poop. They might want to look at your poop if you have noticed changes in it.

- Breath test

The H. pylori breath test is an accurate test for diagnosing an active H. pylori infection. For the test, you’ll drink a flavored solution containing an organic chemical compound called urea. If H. pylori bacteria are present in your digestive tract, they will break down the urea and convert it to carbon dioxide. The carbon dioxide will come out in your breath. When you breathe into a bag, healthcare providers will be able to measure it.

Treatment

Ulcers can heal if they are given a rest from the factors that created them. Healthcare providers treat uncomplicated ulcers with a combination of medicines to reduce stomach acid, coat and protect the ulcer during healing and kill any bacterial infection that may be involved.

- Medical management

- Antibiotics. If H. pylori was found in your digestive tract, your healthcare provider will prescribe some combination of antibiotics to kill the bacteria, based on your medical history and condition.

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). These drugs help reduce stomach acid and protect your stomach lining. PPIs include esomeprazole, dexlansoprazole, lansoprazole, omeprazole, pantoprazole and rabeprazole

- Antacids. These typical over-the counter medications aid in the neutralisation of gastric acid. They may provide some symptom relief, but they will not heal your ulcer. They may potentially interact with some antibiotics.

- Cytoprotective Agents: These medications cover and protect the lining of your stomach.

Sucralfate and misoprostol are two of them.

- Surgical management

- While most ulcers may be managed satisfactorily with medicines, certain more serious ulcers may necessitate surgery. Ulcers that bleed or have perforated your stomach or intestinal wall will require surgical correction. A cancerous ulcer or one that is blocking a route must be surgically removed.

- In extreme situations, a recurring ulcer may be treated surgically by cutting off portion of the nerve supply to the stomach that creates stomach acid.

Complications of Peptic Ulcer Disease

- Internal bleeding: While most people with ulcers do not experience bleeding, it is the most common consequence. Anemia or serious blood loss can result from a slow bleeding ulcer.

- Perforation: A constantly eroding ulcer by acid might eventually produce a hole in the stomach or intestinal wall. This is both excruciatingly uncomfortable and hazardous. It permits germs from the digestive system to enter the abdominal cavity, which can lead to peritonitis, an infection of the abdominal cavity. The infection is therefore at danger of spreading to the rest of the body (septicemia). This can result in sepsis, a potentially fatal illness.

- Obstruction: An ulcer in the pyloric channel, the thin conduit that connects the stomach to the duodenum, can form an obstruction, preventing food from passing into the small intestine. This is possible after the ulcer has healed. Ulcers that have healed may develop scar tissue that causes them to grow. An ulcer large enough to impede the small intestine might halt digestion, resulting in a variety of negative effects.

- Stomach cancer: Some stomach ulcers might progress to cancer over time. When your ulcer is caused by H. pylori infection, this is more likely. H. pylori is a contributory cause of stomach cancer, which is luckily infrequent.

Prevention

- If at all possible, limit your usage of NSAIDs. Consider whether acetaminophen might be used instead.

- If you are using NSAIDs for medical reasons, see your doctor about lowering your dosage or switching medications.

- To protect your stomach lining, your doctor may also prescribe another medication to take in addition to NSAIDs.

- Reduce other irritants, such as smoking and alcohol consumption, that may lead to too much stomach acid or damage your stomach lining.

- Test your breath for H. pylori to see whether you have an overgrowth of the bacterium.